Key takeaways

A hedge fund is an investment vehicle that pools money from many individuals and organizations.

Hedge funds invest in a wide range of liquid and illiquid securities and use different trading approaches across the various hedge fund strategies.

Hedge funds are high risk and not everyone is eligible to invest in them, so you should speak to a financial professional to determine if they’re right for you.

The term “hedge fund” applies to a variety of investment strategies that offer the potential for greater portfolio diversification and enhanced returns.

Hedge funds are not considered appropriate for every investor, says Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director for U.S. Bank Asset Management. “More assertive investors may benefit most,” he says. “These are more complex strategies, so investors have to be aware that in trying to ramp up returns, they may be taking on more risk.”

“Investors may find value in hedge funds. It’s important to recognize that there’s a large variation among hedge fund strategies. You should carefully assess your options and try to find the most appropriate strategy to fit your portfolio.”

Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director, U.S. Bank Asset Management

If you’re considering adding hedge funds to your portfolio, you’ll want to consider the range of available investment strategies to identify those that are consistent with your overall investment strategy and risk tolerance.

What is a hedge fund?

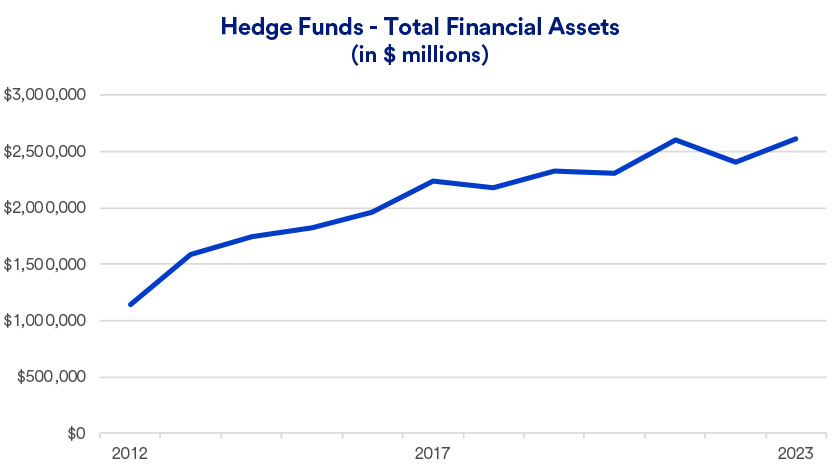

A hedge fund is an investment vehicle that pools money from many individuals and organizations and invests in a wide range of liquid and illiquid securities in the hopes of high returns. They first came into existence in the 1940s, when wealthy investors were looking for ways to include assets in their portfolios that did not closely correlate with the performance of traditional investments. Hedge funds gained more mainstream popularity in recent times, with more than $2.5 trillion invested today.

Hedge funds are managed differently from traditional stocks, bonds or mutual funds, so they fall under the category of “alternative investments.” Until recently, hedge fund access was limited to pension plans, large institutions that manage money for individuals or organizations, and clients with millions of dollars to invest. Today, regulatory changes provide individual investors hedge fund access.

“Investors may find value in hedge funds,” says Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director for U.S. Bank Asset Management. “It’s important to recognize that there’s a large variation among hedge fund strategies. You should carefully assess your options and try to find the most appropriate strategy to fit your portfolio.”

It’s important to note that many hedge funds are considered a high-risk investment, so investors need ensure they’re comfortable with this risk. “Hedge funds tend to be very complex, so it’s important to understand what you own and why you own it,” says Haworth.

Who can invest in hedge funds?

If you’re considering investing in a hedge fund, you’ll have to meet eligibility requirements, which vary from fund to fund and are guided by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Most notably, individual investors typically must have a high net worth and/or a significant amount of money to invest.

What does a hedge fund manager do?

A hedge fund manager, which can be an individual or a firm, is critical to the success of a hedge fund. They are responsible for the hedge fund’s overall investing strategy and operations.

One of their responsibilities is to allocate the investment dollars they oversee. They have significant flexibility in how they do this, which is why it is so important that they have extensive knowledge and experience.

“Be aware that certain hedge fund managers have a track record that demonstrates the meaningful value they offer,” says Haworth, “but others have not established extensive or competitive track records.”

Ensure that the hedge fund manager you’re considering undertakes sourcing and due diligence processes to choose funds that are likely to meet the stated risk and performance targets. They should also identify funds that are well-suited for their clients’ goals and constraints. This requires significant industry knowledge, resources and time, because managers must constantly monitor hedge fund launches and closures.

What are the potential benefits of hedge funds?

Because hedge funds are managed differently than traditional mutual funds, there are a few potential benefits to note.

Attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Many hedge funds emphasize their ability to generate competitive returns while effectively managing market volatility.

Diversification benefits in down markets.

The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite, a measure of hedge fund performance, shows that as a group, hedge funds exhibited less severe declines in recent periods when the broader stock market, as measured by the S&P 500, sustained significant losses.

Variable market exposure.

Since there are a wide range of hedge fund strategies, hedge funds can be positioned to either capitalize on a strong market (by exposing more than 100% of the portfolio to equities) or protect the portfolio by holding less than full market exposure.

Ability to assume significant short positions.

Hedge funds regularly use short selling to capitalize on a potential decline in value for a specific security.1

The possibility of upside regardless of market conditions.

Hedge fund managers have lots of flexibility to pursue attractive investment opportunities – during bear and bull markets alike – across security types, economic sectors and geographic regions, using a variety of sophisticated strategies.

Historical hedge fund performance

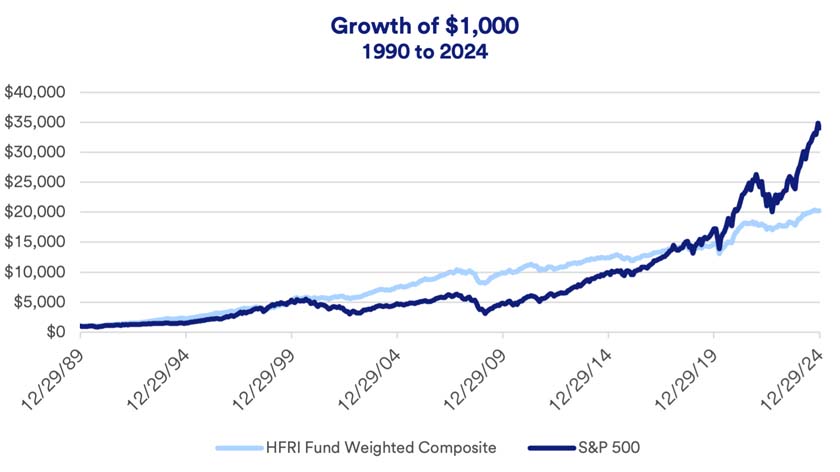

From 1990 to 2024, a period when traditional stock indices experienced substantial appreciation, hedge funds generally tracked with equity markets by managing portfolio risk that mitigated losses. During periods of significant stock declines – such as the early 2000s dotcom bubble, the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 correction – hedge funds saw more stable performance.

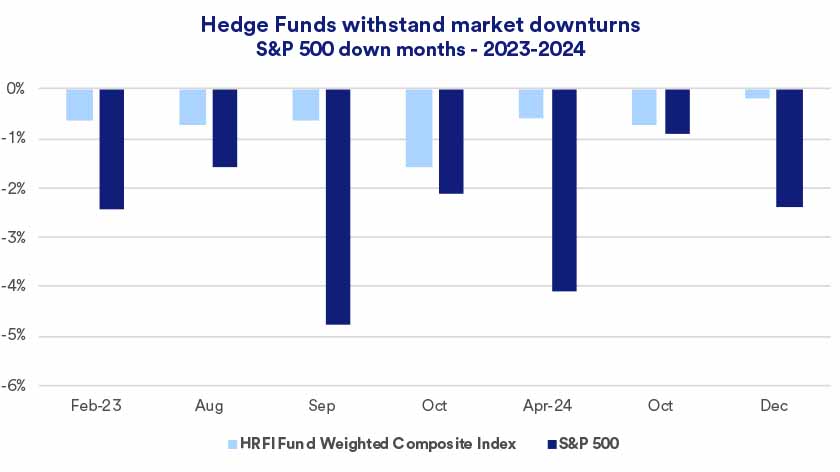

Performance results from 2023 and 2024 provide examples of how hedge funds potentially limit the impact of down markets. While stocks in general performed well during this time, they suffered losses in seven different months. In each of those months, hedge funds (represented here by the HRFI Fund Weighted Composite Index) limited losses.

The graph below, shows the growth of $1,000 invested in hedge funds (as represented by the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite) compared with $1,000 invested in the S&P 500 Index over the past 34 years. Note that until 2020, hedge funds outperformed stocks. In both 2023 and 2024, the S&P 500 enjoyed total returns exceeding 25%. Hedge funds did not keep pace during these periods of outsized equity market performance, but may be well positioned for potentially volatile periods.

What are the potential disadvantages and risks of hedge funds?

Hedge funds are widely seen as high risk, so if you’re considering investing in them, it’s important to understand these risks. They include:

Their speculative nature.

Because hedge fund managers have so much flexibility in how they structure their portfolios, your money could be used for speculative types of investment strategies. Short selling, the use of leverage and derivatives can all add to the risk, even though they’re often used with the intention of moderating risk.

High fees.

Hedge funds typically charge both a management fee and performance fee. Management fees are typically between 1% and 2% annually, regardless of performance. Most funds also charge performance fees ranging from 15% to 20% of the profit that the fund generates each year. “You want to be selective in choosing a hedge fund to include in your portfolio and be certain you are being adequately compensated in terms of return potential for the costs you bear,” says Haworth.

Lack of liquidity.

Hedge funds are generally illiquid and are therefore considered a long-term strategy. They may apply various restrictions that affect your liquidity or investment potential. These include lockup periods (when you can’t liquidate shares), withdrawal gates (which give the fund manager the right to limit or halt fund redemptions during certain periods) and side pockets (which may restrict some new investors from participating in certain fund holdings). These tools may be used when the liquidity offered to clients doesn’t match the liquidity of a portfolio’s underlying securities due to periods of market stress.

Complex tax reporting.

Money held in a taxable account can be subject to short-term or long-term capital gains tax or other types of investment taxation. Each year, hedge fund investors receive a form K-1 with tax reporting information. However, in many cases, those forms are not provided before the standard April 15 tax filing deadline, which may require investors to file a tax extension. “It’s important that investors are aware of how hedge fund tax reporting can be more complicated than what they’ve become accustomed to with more traditional investments,” Haworth says.

What are some hedge fund investment strategies?

Every hedge fund uses different investment strategies, so doing your due diligence when looking for a hedge fund to invest in is critical. You want a fund that not only has a solid performance and risk management track record but also fits your specific investment objectives. Here are six broad types of hedge funds:

Equity hedge.

This is the most common strategy and comprises of equity long/short funds. It involves buying undervalued stocks (long positions) and selling stocks considered to be overvalued (short positions). By using hedging strategies, a fund can often limit volatility compared with its competitive stock index. “Sector hedge fund strategies may look particularly appealing based on recent performance,” says Haworth. “We’re seeing a wide dispersion in performance among stocks within sectors such as information technology and health care.” This creates opportunities for long/short fund managers to profit from “winners” and “losers” in each sector.

Long/short credit.

These funds take both long and short positions in the bond market. Much of the return comes in the form of coupon payments that bonds generate, plus some from capital appreciation (in long positions) or depreciation (in short positions). These funds invest across various investment grades, maturities, types of collateralizations and all levels of the capital structure that a company uses to finance its operations and growth.1 “Some managers pursue complex credit strategies that we’ve seen add value to portfolios,” says Haworth. “What’s attractive is that they not only buy credits, but have the flexibility to ‘short’ against them as well.”

Event driven.

These funds take equity or fixed-income positions based on an event that’s expected to increase a security’s value. Events can include company mergers, a firm spinning out a subsidiary unit or a company’s capital restructure. Often referred to as “special situations,” these events are key in determining a stock or bond’s value.

Relative value.

These funds seek to exploit pricing differences of related financial instruments. They typically have less exposure to stock and bond markets compared with equity hedge and long/short credit strategies. Most of these funds focus on distressed debt and sovereign bonds, along with high yield and investment-grade bonds.

Global macro.

These funds have the broadest investment mandate of all hedge fund strategies. They can invest in virtually all asset classes, markets and types of investments. Managers assess the global economic landscape and seek to profit from imbalances or dislocations due to macroeconomic and geopolitical events. Because managers have significant leeway in structuring a portfolio, these funds can generate attractive returns during periods of market uncertainty. “We’ve been in a period of greater potential volatility, which can create better opportunity for funds like these to add value,” Haworth notes.

Managed futures.

These hedge funds used strategies focused on trading futures and forward contracts on all types of assets. Their objective is to generate an uncorrelated return relative to stock and bond markets. Trading is usually directed by computer-driven algorithms, rather than a fund manager. These models are based on algorithms that try to identify trends that could affect specific assets. Funds then take positions based on the expected direction of an asset’s price. Managed futures are among the most liquid of hedge fund offerings.

Is investing in hedge funds right for you?

The potential benefits of investing in hedge funds are significant, but so are the potential risks. “It’s important to work with a professional to consider whether specific hedge fund managers can add enough value to your portfolio for the risk you take on,” says Haworth.

Talk with your financial professional and take the time to understand how hedge funds work, the expected returns, risks and fees. They can help you determine if investing in hedge funds could enhance your portfolio and help you achieve your investment objectives.

Learn how we approach your long-term investing success.

Based on our strategic approach to creating diversified portfolios, guidelines are in place concerning the construction of portfolios and how investments should be allocated to specific asset classes based on client goals, objectives and tolerance for risk. Not all recommended asset classes will be suitable for every portfolio. Diversification and asset allocation do not guarantee returns or protect against losses.

Indexes shown are unmanaged and are not available for direct investment. The S&P 500 Index consists of 500 widely traded stocks that are considered to represent the performance of the U.S. stock market in general. The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index is a global, equal-weighted index of over 1,400 single-manager funds that report to HFR Database. Constituent funds report monthly net of all fees performance in U.S. dollar and have a minimum of $50 million under management or a 12-month track record of active performance. The HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index consists of over 800 constituent hedge funds, including both domestic and offshore funds. Fund of Funds invest with multiple managers through funds or managed accounts. The strategy designs a diversified portfolio of managers with the objective of significantly lowering the risk of investing with an individual manager. The Fund of Funds manager has discretion in choosing which strategies to invest in for the portfolio. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based benchmark that measures the investment grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market, including Treasuries, government-related and corporate securities, mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities and commercial mortgage-backed securities.

Accredited investor: For individuals, the requirement is generally met by a net worth that exceeds $1 million (excluding primary residence and any related indebtedness), income in excess of $200,000 (individually)/$300,00 (jointly with spouse) in the two most recent years with an expectation of the same in the current year, or individual has a Series 7, 65 and/or 82 securities license(s). (Relying on joint net worth or income does not mean securities must be jointly purchased.) For entities (including trusts, non-profit corporations exempt under s. 501(c)(3), LLCs, LLPs, corporations, etc.), the requirement is generally met with if the entity has assets in excess of $5 million (assuming the entity was not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities offered), or when all of the entity owners are accredited investors. Please refer to Rule 501 under the Securities Act of 1933 for the complete definition. Qualified Client: The requirement is generally met if the investor has at least $1M under investment with the fund manager, the investor has a net worth of more than $2.1 million (excluding primary residence and any related indebtedness), or the investor is a Qualified Purchaser (see below). Please refer to Rule 205-3 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 for the complete definition. Qualified Purchaser: For individuals, the requirement is generally met when the investor owns (individually or jointly) $5 million or more in investments. [Relying on joint ownership of investments does not mean securities must be jointly purchased.] For entities (including trusts), the requirement is generally met if the entity owns $25 million or more in investments; the entity owns $5M or more in investments AND it is owned by two or more natural persons who are related as siblings/spouse; or all beneficial owners of the entity are each Qualified Purchasers. Please refer to Section 2(a)(51) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 for the complete definition.

Tags:

Explore more

Is investing in an initial public offering a good idea?

It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement surrounding IPOs. Review these common misconceptions before investing.

Personalized investing guidance aligned with your goals.

Let us help you craft a portfolio that reflects your goals, time-horizon and values.