4 benefits to paying foreign suppliers in their own currency

Addressing financial uncertainty in international business

In our volatile global economy, few businesses are exempt from the risk of changing foreign exchange (FX) rates. In fact, every organization that does business in a foreign country or even conducts transactions with foreign companies faces currency exposure and the associated risk of volatility. So how can they stay ahead of markets that can swing as swiftly as the next headline? For many corporate treasurers, the answer involves hedging.

Risk management strategies allow multi-national organizations to identify their risks and reduce their exposure to them. Currency hedging can mitigate the risks created by FX market volatility, including reducing earnings volatility and protecting the value of future cash flows or asset values.

“You should be informed on what’s happening in the FX markets,” says Chris Braun, Head of Foreign Exchange at U.S. Bank. “But for a corporate treasury team, the focus of any currency hedging program should be on the reduction of risk, not on trading the market.”

In fact, there is a tangible value to this kind of risk management. A five-year study of more than 6,000 companies from 47-countries found that FX hedging was associated with lower volatility in cash flows and returns, lower systematic risk and higher market values (Bartram, Brown, and Conrad). In a landmark study of U.S. companies, Allayannis and Weston showed that FX hedging increased market valuation by 4.87 percent.

“From a corporate treasury standpoint, the goal is to provide stability, enabling better planning and forecasting,” Braun explains. “Public companies really need to be careful about forecasting earnings and making sure that they are messaging a probable earnings per share estimate, and hedging helps them do that. Privately owned companies have shared concerns about stability/predictability of cash flows and will opt to hedge as well.”

Although there are three fundamental hedging instruments – spot, forwards and options – and a large number of combinations to apply them, the fundamentals of FX hedging can be simplified by identifying the source of the risk and focusing on the organization’s main objective, which is either reducing the volatility of cash flows in functional currency terms or the volatility of earnings in reporting currency terms.

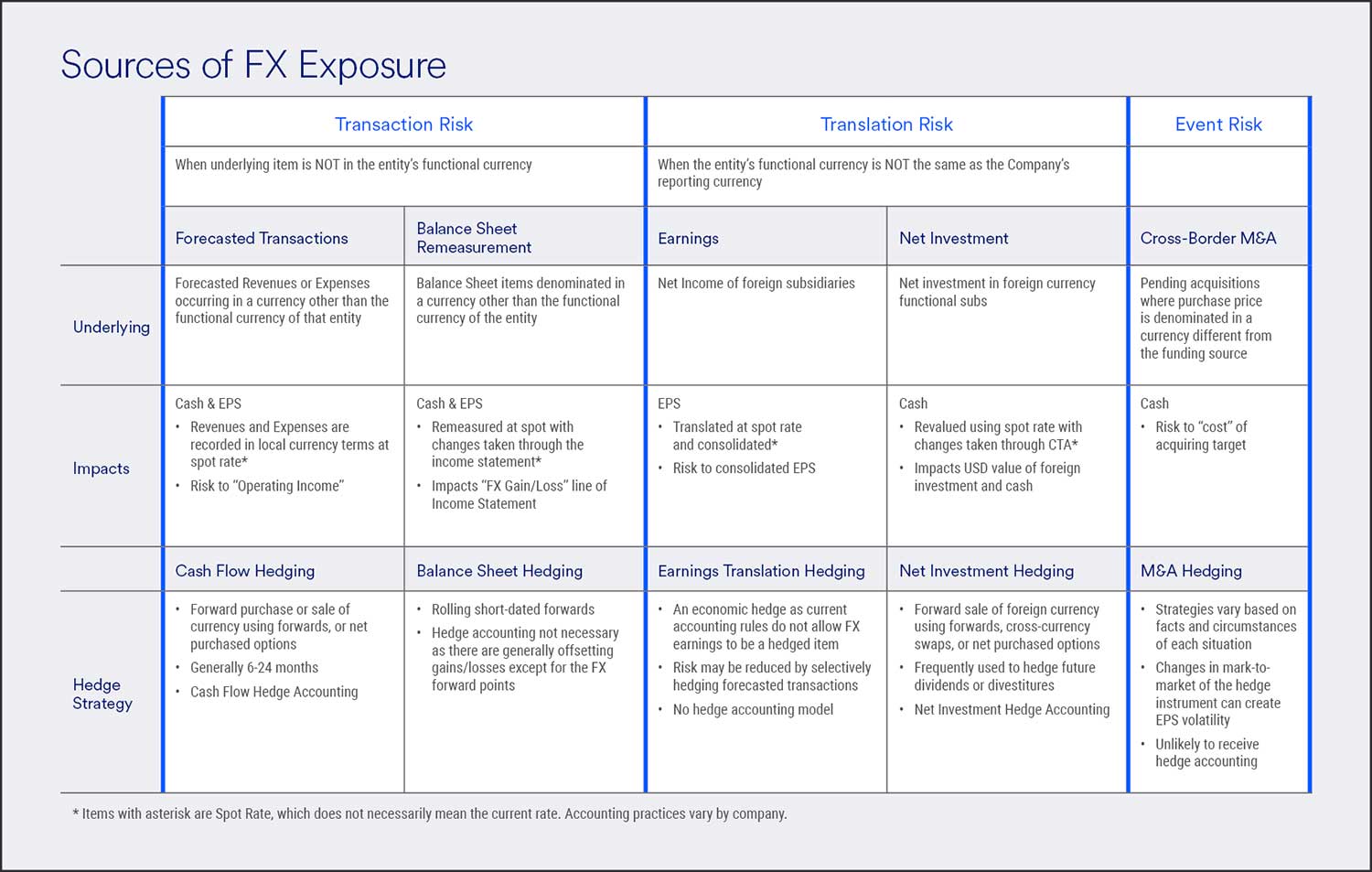

Despite the many complexities of international business, those sources of risk can also be broken down into five categories, each one requiring its own solution:

In order to categorize these exposures, Braun provided the table below, which identifies the type of risk along with the associated impact to the income statement or balance sheet. Using that combination of factors, the grid identifies which strategies are commonly utilized in the associated accounting model.

“You should categorize and think about each of these risks and how they relate to each other before you dig too deep into any one solution to a problem,” he explains. “Before focusing on the solution, you really need to understand the underlying problem and how it impacts the income statement and balance sheet of the company.”

Although an organization’s risk scenarios may change over time, two of the most common hedging strategies often go hand in hand. Cash flow hedging and balance sheet hedging involve similar underlying transactions, depending on the given transaction’s timing and accounting considerations.

The passage of time and occurrence of when the sale or purchase is actually recognized on the income statement and balance sheet connects the two concepts. For example, when a sale is forecasted, it hasn’t happened yet, and as such, is not recorded on the income statement. Because there is nothing yet on the financial statements to hedge, that forecasted transaction requires a cash flow hedge. In the instance of forecasted revenue, once that sale actually occurs, then it becomes a balance sheet item (accounts receivable) and requires a balance sheet hedge.

A company might hedge at the point where the transaction is forecasted or at the point when it is recorded – or both – depending on its risks and accounting goals.

“Many companies think that they have better data on balance sheet hedging,” Braun says. “It also doesn’t have as much complexity from an accounting standpoint, so balance sheet hedging tends to be an easier place to get started.”

With balance sheet hedging, the company is re-measuring the underlying foreign currency receivable (in the example of a foreign sale) on a dollar-value set of books. The foreign receivable is marked to market in dollar terms for FX fluctuations and the gain or loss in dollar terms goes to the other FX gain or loss line on the income statement. Balance sheet volatility is easy to hedge with short term rolling forward contracts. In this case, hedge accounting is not needed, because you want the change in the mark to market of the hedge to flow through to the income statement, offsetting the impact of the spot change in value of the underlying asset (or liability).

Cash flow hedging, by contrast, is used on forecasted transactions, and thus, hedge accounting is important in this case. To reiterate, the focus on hedge accounting is due to the fact that the forecasted transaction does not yet show up on the income statement, which in turn means that any changes in FX rates will not impact that period’s net income. Therefore, the hedge’s mark to market does not affect net income until the underlying transaction is recorded in earnings. As such, the hedge does not create profit/loss volatility during the hedging period as the change in fair value is recorded in Other Comprehensive Income (OCI), but the associated gains/losses are released from OCI to the income statement when the underlying transaction is recorded in earnings to protect the margins of the underlying forecasted transaction.

How does it all work together? Consider a U.S. based company with a five-year contract paid in Euros to manufacture windshields for a German automaker. While there is a predictable stream of Euro cashflows, if the Euro depreciates, the manufacturer might not be able to protect its margins – especially if its cost base is in U.S. dollars and doesn’t offset the revenue decline caused by the Euro fluctuation.

Using cash flow hedging in this example makes sense. It protects margins related to the contract while not introducing volatility by hedging a transaction which has not yet been recognized as a sale or expense on the income statement of the manufacturer.

“As companies become more global, or individual contracts become larger relative to the size of the company, then it becomes increasingly relevant to use cash flow hedging to mitigate that risk to their profit margins,” Braun says.

If the manufacturer decides to shift its cost base to Europe by building a factory in Europe at its EUR functional European subsidiary and funds it with an intercompany Euro denominated loan from the USD functional Parent Co., the Parent will now have a EUR asset on its USD balance sheet. It can easily hedge that loan’s USD-equivalent value by using a balance sheet hedge. This example illustrates how and why the accounting may be tricky. Left unhedged, this EUR denominated intercompany loan will be remeasured to earnings each period on the USD books of the parent without a corresponding offset from a hedge.

When the firm starts manufacturing and selling the windshields, they may start billing out of the EUR subsidiary to better align their revenues with their expenses. In doing so, they will no longer have forecasted transactions that qualify for cash flow hedge accounting, since the transactions will be denominated in the same currency as the functional currency of the legal entity. By aligning their revenues and expenses, they have protected their margins, but they still haven’t eliminated their exposure to currency fluctuations because the USD functional parent company now owns a European entity that is accruing profits in EUR rather than USD. The risk now shifts to the translation of foreign earnings and cash (Earnings Translation and Net Investment are now on the table).

“Each of these concepts connects to the other and understanding the accounting impact is really the starting point for building a good currency risk management program,” Braun says.

Although cash flow and balance sheet hedging comprise the vast majority of FX hedging, the complexities of international business also require the understanding of three other kinds of risk management.

When considering an FX hedging strategy, remember to think about the economic and accounting impact. “What happens to the income statement if I do hedge or if I don't hedge? And what happens to the balance sheet? What's the significance of hedge accounting?” Braun says. “These are all important questions because these things all tie in together.”

With regulations that vary from country to country, multiple currencies to manage, and processes that are vastly different from domestic trade, international trade is a complex, fast-moving arena. This article briefly touched on the five main sources of foreign exchange risk. When addressing the volatility of foreign exchange rates, decision makers engaged in international business should consult with knowledgeable treasury management and foreign exchange banking professionals to understand how those risks affect the company’s financials, liquidity and cash position.

Connect with an expert to help your business with global cash flow, foreign exchange and international financing challenges.

Related content

Disclosure:

Note that the foregoing is not applicable to consumers, nor is foreign exchange hedging appropriate for all businesses. These transactions are subject to regulatory qualifications; U.S. Bank cannot enter into hedging transactions with you unless all regulatory requirements are satisfied. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer, a commitment, or solicitation to engage in any products or transactions and is not intended as financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice. All hedging transactions are arm's length transactions, entered into on a principal basis, to be negotiated by each party acting in its own best interests. Before entering into any transaction, you, along with your own financial, legal, tax, accounting and other professionals, should conduct a thorough evaluation of any proposed transaction and determine whether or not this transaction is right for you. Note that hedging transactions are subject to market conditions at the time of trading, final credit approval and agreement upon all terms. The content of the foregoing article is provided for your informational purposes only and is not derived from research conducted by U.S. Bank or any of its affiliates. The information is derived from internal and external sources that we believe are reliable, but we do not warrant their completeness or accuracy, it is subject to change without notice and we are not responsible for its use or to keep the information updated. Foreign-denominated funds are subject to foreign currency exchange risk. Customers are not protected against foreign currency exchange rate fluctuations by FDIC insurance, or any other insurance or guaranty program. The products and services described herein are available through U.S. Bank National Association and are not bank deposits, are not insured by the FDIC or any federal government agency, nor are they guaranteed by U.S. Bank National Association. Neither we nor any of our affiliates are acting as your agent, broker, advisor or fiduciary in connection with any such transaction, and if we (or any of our affiliates) are otherwise engaged to act in such capacity in connection with other products and services, the engagement will be deemed to exclude any hedging transaction unless we otherwise agree in writing. This disclosure does not outline all risks related to the transactions. Prior to engaging in hedging transactions, please see the ISDA General Disclosure Statement for Transactions, including the Disclosure Statement for Foreign Exchange Transactions, and additional product disclosures provided to you by U.S. Bank National Association prior to the execution of any forward, non-deliverable forward or foreign exchange options.